Share the Lore!

By: Alex Postrado

Is The Will-o’-the-wisp Real?

There is a light that has been glowing since at least the 14th century.

Found near marshes and swamps, this flickering blue flame gave rise to a variety of terms we often encounter in both literature and folklore.

Ghost candles. Ignis fatuus. Fairy lights. And even your Halloween favorite, jack-o’-lantern!

But, perhaps, this elusive being is best known by the name, will-o’-the-wisp.

They are what Princess Merida sees and follows around the forest in the 2012 Disney-Pixar film, Brave.

Sometimes attributed to ghosts and other times considered as fairies, will-o’-the-wisps have long been part of traditional legends and superstitions in numerous countries.

But where did it all start? And is there any truth to their existence?

We’ll find out!

From Darkness Comes a Ball of Light

It’s hard to think of a time when stories about floating lights in forests or secluded places did not exist.

For most of recent history, we’ve been warned about them.

The will-o’-the-wisps.

Believed to come from the proper name Will and the word wisp — meaning, a bundle of hay, presumably used as a torch — the name will-o’-the-wisp can be directly translated to Will-with a wisp, Will of the wisp, or even Will of the torch.

Some experts, however, like to look at the name’s possible connection to the Saxon word “wile” — meaning, trickery or deceit.

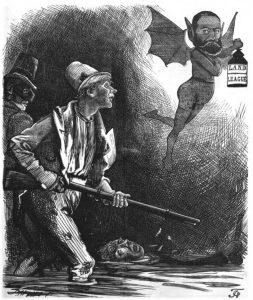

Birthing the idea that there’s a supernatural trickster, holding a torch that produces the enthralling light people have sometimes gotten a glimpse of.

According to the stories, will-o’-the-wisps usually appear at night, before lone travelers, typically over swamps, bogs, or marshes.

They use their beguiling lights to get the attention of their target, initially looking as if harmless — maybe, even playful. But, oftentimes, leading their prey into danger or worse, to their grave.

Though, some accounts claim that that’s not always the case.

Will-o’-the-wisps can also guide wanderers to some hidden treasure or straight to the fairy kingdom — as several consider them to be sprites or fairy-like creatures who simply like to mess around.

That said, you’d probably get a 50-50 chance of living or dying if you’re brave enough to follow a will-o’-the-wisp.

But I bet most people would not dare do that.

The belief has it that even the mere appearance of a will-o’-the-wisp could mean death. A prediction of the demise of either the person who saw the sentient ball of fire or someone close to them.

Why so Many Names?

As mentioned earlier, the will-o’-the-wisp takes on a lot of different names.

This could mostly be credited to the myriad of — at times, contradicting — stories it has graced for centuries.

An example of this would be the name ignis fatuus.

Composed of ignis or fire, and fatuus — meaning, foolish or silly — the term, coined by English Puritan William Fulke in his 1563 Book of Meteors, translates to what he described as “foolish fire that hurteth not“.

An implication that the ethereal floating lights never intended to harm anyone? Likely.

Yet another moniker for the will-o’-the-wisp is corpse-candle.

A name first mentioned by Welsh poet Dafydd ap Gwilym in 1340 as canwyll corff and translated into English by W. Sykes, this marked the first recorded association between the hovering flame and boneyards.

In etiological myths, circulating around England, Ireland, Scotland, as well as nearby regions, the will-o’-the-wisp is frequently claimed to be “the soul of one who has been rejected by hell carrying its own hell coal on its wanderings“.

They call it Jacky Lantern, jack-o’-lantern, or Jack of the lantern — after the usual name of the main character in their tales, Stingy Jack.

As for how it became a U.S. Halloween mainstay is another story.

But, basically, it stemmed from Irish and Scottish people, carving scary faces to their own lanterns — made of turnips and potatoes — to try to frighten off the “real” Stingy Jack and hopefully, other evil spirits, as well.

In Worcestershire, will-o’-the-wisps are known as hobby lantern, Hob-and-his-Lanthorn, Hobany’s Lanthom, or Hoberdy’s Lantern — basically, whichever version works.

It came from the word Hob, which we also see in the term hobgoblin — “a mischievous imp or sprite” — but was once used as a personal name by common people.

The idea, connecting will-o’-the-wisps to fairy-like beings, was adopted — in a similar fashion — by none other than the Bard, himself, William Shakespeare.

He alluded to this through Puck in his A Midsummer Night’s Dream — a prankish fairy “who turns into a phosphorescent glow” to mislead passersby.

In the Americas, however, that “glow” is often referred to as ghost lights, spook lights, or orbs.

Still and all, that only touches the tip of the iceberg.

In fact, in her book, A Dictionary of Fairies, British folklorist K. M. Briggs listed down the abundance of names the tiny, luminous will-o’-the-wisp have had over the years.

Taking note that while all of them might be raising accounts of the same phenomenon, the places where they were observed likely had a huge influence on the variability both in their narratives, moreover their names.

Shedding Light on the Science Behind the Will-o’-the-wisp

Traditional folklore, literature, and cinematic fiction all had a hand in immortalizing the story of the mystifying will-o’-the-wisp.

Sometimes, though, tales like these would get people to wonder whether or not supernatural entities — like, in particular, the will-o’-the-wisp — truly exist.

And to answer that, we’d have to hear what science had to say.

For a very long time, the explanation for this strange phenomenon was kept a mystery, waiting to be unveiled.

Researchers and witnesses, alike, have put forward several theories over the years as to what could possibly cause the existence of the will-o’-the-wisp.

Some suggest that bioluminescence could be the answer we’re looking for.

And there’s — indeed — quite a long list of organisms that could produce light by themselves: some of which are certain species of fish, fungi, bacteria, fireflies, and glowworms.

But, among those, fireflies and glowworms would be the most plausible candidates.

If only fireflies produce blue lights instead of greenish ones. Or if glowing female glowworms can fly and flying male glowworms can glow.

Confused yet? Here’s another theory!

Barn owls may also be the explanation, according to some.

Apparently, when these birds fly over swampy areas, their wings can “reflect light from the moon or other sources“. But would that look like floating blue lanterns?

Well, Alessandro Volta seems to disagree.

In 1776, he proposed that natural electrical phenomena — such as lightning — combined with existing methane in marsh or swamp gases could cause the appearance of the will-o’-the-wisp.

This concept initially raised eyebrows, but with scientific advancements through the years, it now appears that he was actually more or less correct.

Swamps contain “large, thick deposits of organic decay” that when fermented, releases phosphorus hydrides.

And when methane mixes with those phosphines, you would have the hovering blue lights that disperse when you approach them.

The will-o’-the-wisp.

The ball of light traveled from European marshes to the Americas and other parts of the globe.

Shaping stories that spooked humans for hundreds of years.

Who would’ve thought that they’re somehow real?

References:

Definition of wile Will-o'-the-Wisp: an ancient mystery with extremophile origins? Will-O'-The Wisp: Deadly Fairy Lights The Legend Behind the Will O the Wisp in Brave The Will-O'-The-Wisp and its Folk-Lore Jack-o'-lantern How Jack O’Lanterns Originated in Irish Myth Ghost Lights: Believe If You Dare What causes the will-o'-the-wisp Phosphine