Share the Lore!

By: Alex Postrado

Yōkai: Supernatural Tradition from Japanese Folklore

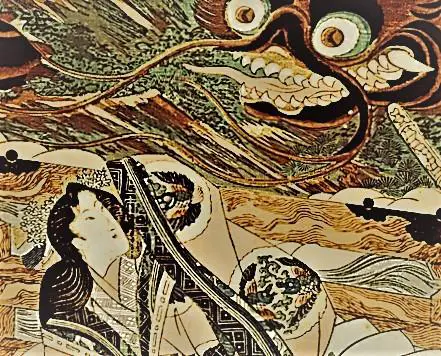

In a world of gods and monsters, there are yōkai.

And as we all know, Japanese folklore is overrun by them.

Simply put, the word yōkai is Japan’s catchall term for all things supernatural 一 be it fairies, ghosts, beastlike creatures, or other fantastical anomalies of the sort.

The turtle-like, river monsters believed to be found all over Japan? They are called kappa and they are yōkai.

The popular, orc-like oni demons? A class of yōkai, as well.

The possessed kimonos called kosode no te? Also yōkai.

And the haunted pillar, sakabashira? Well, you guessed it 一 yōkai!

It seems like, in Japan, just about anything can be attributed to these otherworldly entities.

And how else should it be when the concept of yōkai has been so tightly interwoven in Japanese culture since ancient times?

Rooted in the country’s local belief system and broadly integrated into people’s daily lives today, there is simply no reason why yōkai wouldn’t be everywhere 一 and why knowing about them wouldn’t be interesting.

From the innocuous to the murderous, the godly and the monstrous 一 behold, the history and subtleties of yōkai.

Into the Fantastical World of YŌKAI

If there is a concept broader than any other supernatural belief there is in this world, then it is likely to be the concept of yōkai.

See, unlike how we use the English word “monster“ to exclusively refer to “frightening imaginary beasts” and the term “supernatural phenomenon” to cite “things or situations that are beyond scientific understanding“, the word yōkai can’t be defined in one go.

In kanji, yōkai is translated into “attractive” and “calamity”, as well as “apparition”, “mystery”, and “suspicious”.

Though in recent years, the term is more commonly associated with spirits, the door into the world of yōkai is also open to other mystical entities, objects, and occurrences.

This is greatly due to the origins of yōkai.

If we look into it, we would see that much of it is molded from animism 一 the belief that places, phenomena, creatures, and inanimate objects alike, all possess a “distinct spiritual essence” 一 sometimes regarded as a “soul”.

Each of these souls has a personality of its own and can, therefore, feel and behave uniquely.

In animism, it is believed that there are peaceful and protective, fortune-bringing spirits. They are called nigi-mitama.

And in the same way, there are ara-mitama 一 the term used for malevolent, affliction-heralding spirits.

Only when a spiritual essence falls into neither category, then are they considered yōkai.

But, over the centuries, yōkai evolved into an all-embracing concept that carries influences not only from animistic principles but also from the rich history of Japan and the cultural periods the country has lived through.

The History of the YŌKAI Myth

As mentioned, while the yōkai myth is undeniably heavy on animism and nature worship influences, it is also profoundly impacted by things that happened in the past.

For instance, ancient-time Japan witnessed an abundance in yōkai references in literary works like the Nihon Shoki 一 in English, The Chronicles of Japan 一 and the Kojiki, an 8th-century exposition of early Japanese myths and oral traditions.

This was the reason why yōkai persisted in the following centuries.

And when the Heian period came, the appearance of yōkai and other mystical phenomena in prominent texts 一 including Japan’s oldest Buddhist setsuwa collection, Nihon Ryōiki 一 further passed the yōkai myth to later generations.

All the way to the end of the Middle Ages, the description of yōkai remained vague.

Others even say that there was a general lack of visual interpretation of yōkai in Medieval-era Japan 一 a thing that changed only when the “Golden Age” of yōkai arrived during the Edo period.

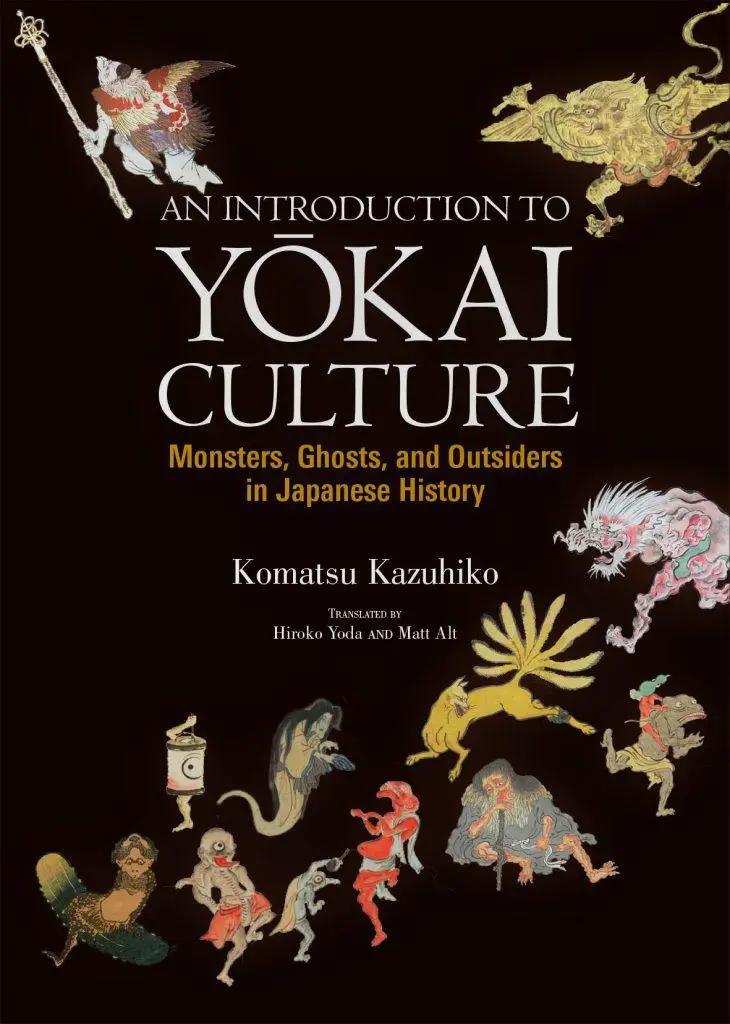

Artists like Toriyama Sekien were to thank for this, as he, along with other folklorists scoured Japan to rescue dying yōkai tales and illustrate the characters “at a time when oral traditions were vanishing“.

Sekien was also responsible for expanding the list of the yōkai we know today 一 by inventing new yōkai inspired by either existing folklore or his own imagination.

The Meiji period came blasting with Western ideas, which inevitably got its way into the yōkai myth.

Soon, more and more western stories were adopted by Japanese folklore. And this influenced the creation, reshaping, and worst, erasure of several yōkai.

Fortunately, the rise of Mizuki Shigeru’s 1960 manga series GeGeGe no Kitarō revived the almost-forgotten yōkai narrative.

Television and other forms of media also contributed to the public’s familiarity with yōkai, while urban legends also began being referred to as “modern yōkai“.

Of course, the rest is history!

And now, there are virtually far too many yōkai in Japanese folklore than most of us can imagine.

So, how do we know which is which when it comes to yōkai?

Types of YŌKAI

With the existence of a whole gamut of yōkai in Japanese folklore, many would understandably try to divide them into more digestible categories.

Folklorist Tsutomu Ema was among those who set out 一 proposing that yōkai can be indexed into 5 types based on their “true form”.

Yōkai that were originally human; those that were originally animal; originally plant; originally an object; or originally a natural phenomenon.

Others, on the other hand, take inspiration from Greek mythology and divide yōkai into several types based on their location or on whatever phenomena they are associated with.

For example, in the book Sogo Nihon Minzoku Goi 一 A Complete Dictionary of Japanese Folklore, in English 一 yōkai fall under any of these 8 types:

First, the dōbutsu no ke 一 those associated with animals, whether real or imaginary.

The second type is called oto no ke 一 yōkai that are linked with sound.

Michi no ke compose the third type and they are those associated with paths.

The fourth type belongs to the snow-related yōkai, known as yuki no ke.

The fifth involves the umi no ke 一 yōkai that are typically found in the sea.

Those connected with trees and other plants 一 the ki no ke 一 make up the sixth type.

Next is the mizu no ke 一 yōkai linked with water.

While the last type is reserved for the mountain-related yōkai, called yama no ke.

If 一 for some reason, though 一 you prefer to arrange yōkai by larger categories, you can always go for the two, basic types of yōkai:

The shapeshifting ones and those that aren’t.

Or if you want something more diverting, you can opt for these 4 types:

The yūrei 一 yōkai that are basically spirits of those who died, like the ameonna, the “rain woman” that licks raindrops from her palms.

The obake or bakemono 一 the shapeshifting type of yōkai, like the spider woman, jorōgumo.

The tsukumogami 一 tools that have “acquired a kami or spirit“, like the kasa-obake, the old, one-eyed umbrella.

Or the choshizen 一 yōkai linked to strange phenomena that are not caused by a specific supernatural entity.

In the end, though, there is no one way of categorizing yōkai.

With the seemingly ever-dynamic nature of yōkai lore, it is likely that the types that we know today would only continue to branch out even further.

Inspiring artists and creatives in the process, as they go over the growing number of yōkai known right now 一 from the shapeshifters, the demons, the tricksters, the ghosts, the monsters galore, and more.

References:

Yōkai: Fantastic Creatures Of Japanese Folklore A Brief History Of Yokai Yokai: Ghosts & Demons Of Japan Yōkai: Everything About Japanese Monsters Yokai: Discover The History Of Japan’s Legendary Monsters Yōkai - Myths And Folklore Yōkai Types