Share the Lore!

By: Alex Postrado

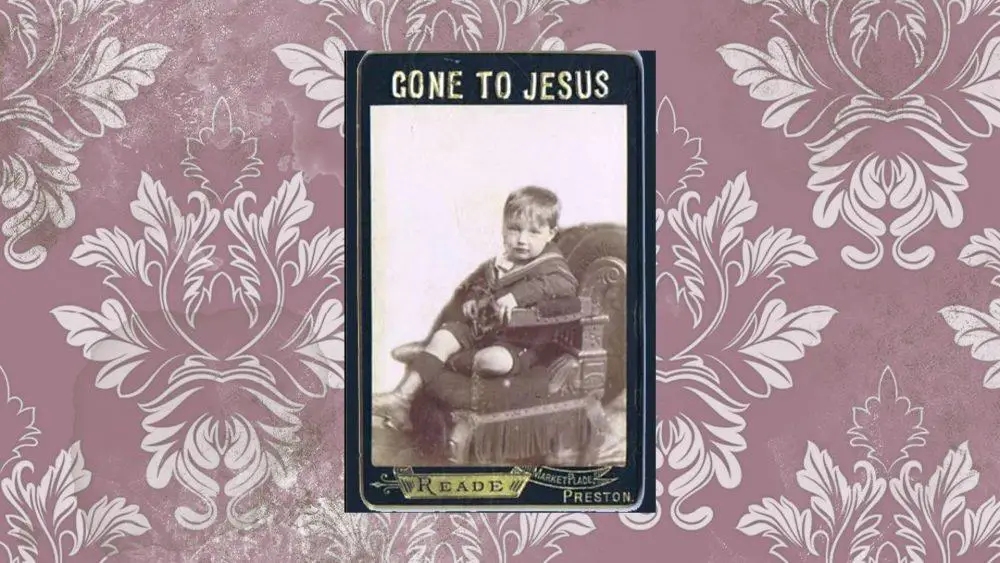

Into The Macabre Victorian Practice Of Photographing The Dead

The Victorian era was — let’s just say — a strange time to be alive.

There were many things from that period that people, nowadays, would find esoteric — or at times, even full-on bizarre.

Like how fascinated the Victorians were by ancient Egypt, to the point that they literally unwrapped mummies for their after-dinner entertainment.

Or how, back then, you could actually make a living out of robbing graves.

There were other peculiarities back in Victorian England. However, the thing that these two examples share in common is the seemingly quotidian way people from that time approach the concept of death — which, to set the record straight, was less of a mere “concept” to them and more of everyday reality.

And as a way to cope with that — to embrace death as just “another part of life” — another peculiar, yet way more sensible, practice arose.

Emerging out of the people’s grief and sentiments about death, a thing that is known as postmortem photography was ultimately born.

DEATH IN THE VICTORIAN ERA

Although some of us may imagine the Victorian era as a time of prosperity, fancy clothes, and rapid industrialization, the reality for the majority of the people from that period was — in truth — far less ideal than this.

More than three-fourths of Victorian society was made up of the working class.

And aside from their poor living and working conditions — epitomized by the rampant child labor practices of that time and the polluted and overcrowded cities the Victorians lived in — there was one thing that made their lives conspicuously less-than-stellar:

The fact that death was almost always in their faces.

It was a time before vaccines, antibiotics, and proper knowledge of hygiene. And so, disease outbreaks happened frequently and were “routinely fatal.”

Because most Victorians could not afford the luxury of seeing a doctor, staying in the comfort of their homes, or eating a more balanced diet, the average life expectancy at birth from that time was particularly low — 40 years old for men and 42 for women.

Even much worse was the death rate for children and infants, which peaked at 46% sometime in the 1800s!

So, how did they deal with that? Well, from the frighteningly familiar relationship of Victorian England with death sprang up a couple of elaborate mourning rituals that aimed to capture the likeness of life.

FROM PAINTED PORTRAITS TO PHOTOGRAPHS

Unsettling as it is, the Victorians did not have much choice as to their ultimate fate. They had to learn to move forward regardless of the rampant deaths and cope with their grief in ways they know how.

The rich did this by having their departed loved ones painted on canvas, in art known today as posthumous portraiture.

However, this method was too costly for the poor and the middle class.

Even if they likewise wanted to preserve the image of their deceased, most of them were not able to… until the daguerreotype emerged in 1839.

Dubbed as the “first successful form of photography,” the daguerreotype opened the door for the middle class to commemorate their dead in a way similar to the more expensive process of sitting for a painted portrait.

During this time, Victorian families began posing with their dead loved ones in photos that were printed in silver.

Still quite costly for many, but as the number of daguerreotype photographers rose, the price for each photography session fell just enough for the working class to join in.

And right then, a somewhat morbid — to our modern understanding — mourning practice took off — one that we currently know as death photography.

MIMICKING LIFE THROUGH ART

When the wealthy Victorians immortalized their deceased family members through posthumous portraits, they personalized the mementos by depicting the dead in poses, gestures, and facial expressions they were best remembered by.

But, with postmortem photography, this apparently was not something that could be easily done — if it could be at all.

This was due to the fact that people of that period were literally photographing and posing with actual corpses.

And sure, this may have made the images of the late far more realistic than the ones in paintings, but this also limited the ways they could capture the spirit and character of the once-living subject.

So, came to light a few popular arrangements the Victorians used to “pose” the deceased in ways that could preserve and “mimic the impression of life.”

Among the most common was called the “Last Sleep,” wherein the dead “lay as though in repose,” with their eyes secured shut.

Contrastingly, younger Victorians — children and infants alike — who passed away too soon were not typically positioned in pictures in this manner. Instead, they were photographed, cradled “in the arms of their mother” or guardian.

Finally, if the family requested to have the dead, placed in a more “animated” pose, they would have the corpse “seated in a chair” — at times, with the remaining living family members, gathered beside or around the resting subject.

And in instances when the deceased needed to look more “alive”, a rosy tint was added to the corpse’s cheeks.

Symbols and references that signal death also often find their way into postmortem photographs. So, even when the deceased looked relatively alive, hints of the passing were still in view — commonly through the appearance of “a dead bird, a cut cord, drooping flowers, or a three-fingered grip,” which was a popular reference to the Christian faith’s holy trinity.

POPULARITY AND DECLINE

The era of death photography flourished for almost a century after the invention of the daguerreotype in the late 1830s.

This was boosted by the later introduction of the carte de visite — a type of pocket-sized photograph, which allowed easy mailing due to its size, as well as the cost-effective printing of multiple copies from a single negative.

However, much like every other fad, the macabre Victorian practice of taking pictures of the dead soon met its end as healthcare in Europe advanced and as the life expectancy of people — especially children — began to improve.

Furthermore, one of the main reasons why Victorians participated in death photography was that, to most of them, this was the only chance to acquire a tangible remembrance of the image of their departed loved ones.

But the advent of handheld cameras in the subsequent 20th century changed that.

People can now take photos, not only in death but, more importantly, in life. And with that, the final nail in postmortem photography’s coffin was secured once and for all.

IS DEATH PHOTOGRAPHY FAKE?

Today, there are people who argue that postmortem photography is not actually a real thing — or, at the very least, that most of the photos we have of it online are “fake.”

They point out how a good amount of corpses in supposed postmortems, found in galleries across the web, look very much alive.

But the reason for this is actually far too simple.

It is because quite a number of those people were — in fact — alive when the supposed postmortem pictures were taken.

For years, the internet has been saturated with wrongly labeled photos of Victorian people — posing with props and stands — tagged as postmortem photographs.

And the spread of these images — whether they were “categorized in error” or “intentionally mislabeled” for profitable gains — contributed largely to the confusion that caused some to question the reality of death photography.

But, in truth, both postmortems and posing stand photographs were real, historical relics from our not-so-distant past.

It is just that they are two art forms, which are compared, contrasted, and interchanged a bit too frequently that the lines that separate the facts about each grow hazier with time.

ACT OF TRIBUTE OR MORBID PRACTICE?

As grim as death photography may sound to some people nowadays, the original essence of the practice was actually centered on honoring the dead and preserving their memory.

It was not seen as something ghastly or creepy back then — rather, as something solemn and reflective.

But the way we approach the idea of death today hinders some of us from seeing this grieving ritual from the Victorians’ point of view.

Our contemporary sensibilities want neither to talk nor be reminded of death.

So, now we mostly only take photos of the deceased for police investigations and pathology work. And situations outside of those make photographing the dead less of a tribute or a probe, and more of a taboo — a dated way of commemorating the departed.

References:

Postmortem Photography: An Understanding Of How It Started Photos After Death: Postmortem Portraits Preserved Dead Family Pictures Of Death: Postmortem Photography Taken From Life: The Unsettling Art Of Death Photography “Mirrors With Memories”: Why Did Victorians Take Pictures Of Dead People? Clearing Up Some Myths About Victorian ‘postmortem’ Photographs